Latino Center for Health: Report to Washington State Department of Health

Assessing Promotora Perspectives of Latinx Perceptions and Attitudes regarding COVID-19 vaccines

February 20, 2024

The Latino Center for Health, an interdisciplinary research center at the University of Washington, conducted and completed a qualitative study of 8 telephone interviews with Latinx promotoras across Washington state as a follow-up to its January 17, 2024 report to the Department of Health which examined the perceptions and attitudes of Latinx individuals regarding COVID-19 vaccines. One interview question also asked about their perspectives regarding vaccines in general.

This companion study, including this report, was commissioned by the Washington State Department of Health (DOH). Data collection took place from the period of January 10, 2024 – January 26, 2024. The sample consisted of eight Latinx adult promotoras who worked with Latinx individuals and communities across Washington state, including rural communities.

This report provides important insights pertaining to Latinx attitudes towards COVID-19 vaccines and their motivations in seeking vaccination. While these findings are not generalizable and the sample size is small, findings provide an important lens, clarity and understanding that will help inform the DOH’s planned media campaign to the diverse Latinx population in Washington state.

Though the crest of the pandemic has subsided, the need for COVID-19 vaccinations persists, due to the on-going emergence of new variants, relaxed standards of masking, and the elevated health risks that remain. Leading experts posit additional contributing factors, namely, not enough people are accessing treatments or getting vaccinated as well as waning immunity in the overall U.S population.1. Currently, nearly 1500 individuals in the country die per week due to COVID-19.2 This number represents significant mortality signaling the importance of vigilance in taking steps for protection and safety..

Research has identified that Washington state’s Latinx communities were disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic with Latinx individuals experiencing higher infection, hospitalization and death rates compared with Whites.3

As of January 8, 2024, COVID booster rates among Latinos in WA are the lowest among racial/ethnic groups, with only 5.5% having received the most recent booster, compared to 18.1% of non-Hispanic Whites.4 Recent research conducted by the Latino Center for Health indicates that vaccine hesitancy among Latinos is fueled by persistent concerns regarding vaccine efficacy, safety, and cost.5

This corpus of national and state research provides clear rationale for conducting the original survey study of Latinx adults in Washington state and this companion study. Gathering information from trusted health workers of the community, namely promotoras, was encouraged by the Latino Center for Health as a means to obtain a more nuanced understanding of the perceptions and attitudes of Latinx individuals in the state with regards to COVID-19 vaccinations.

Methods

The study’s method was to conduct 8 individual interviews in either English or Spanish language by an undergraduate research assistant whose first language is Spanish. The interviews took 20-30 minutes to complete in the language preferred by the respondent. The questions posed to respondents mostly followed the pattern of questions presented in the original study. However, they were revised slightly so as to make clear that the promotoras were providing their perceptions of the Latinx individuals they work with, rather than their own personal perspectives regarding COVID-19 vaccinations. Prior to commencement of data collection, study researchers obtained approval from the University of Washington’s Institutional Review Board Human Subject Division. The application contained recruitment material, consent information, and the revised survey questions. These were all approved by IRB and the study was deemed low risk of harm to participants. Representatives from the WA State Department of Health and its collaborating partner, C+C, also reviewed the survey questions and provided input and suggested edits to the interview guide before it was finalized. The research assistant translated the interview guide into Spanish and this was reviewed by team members of the Latino Center for Health.

Recruitment efforts consisted of the Latino Center for Health e-mailing leaders of two community partners of the Center–the Community Health Worker Coalition of Migrant and Refugees, and the Yakima Valley Farm Workers Clinic. The Center requested their assistance in recruiting experienced promotoras by distributing a flyer with information about this project as well as a phone number to call if interested in learning more about the qualitative study. The flyer was available in English and Spanish languages. The trained research assistant reached out to interested community members who called the posted number. She described the interview process further and scheduled interviews with those who consented.

Interviews were conducted over the phone and recorded for transcription purposes. Participants were asked for verbal consent to continue with the recorded interview before any questions were asked. Interviews were later transcribed, and original recordings were deleted. Six interviews were conducted in Spanish while two were completed in English. Participants were compensated for their time in the form of a $40 gift card sent either electronically or by mail.

Thematic analsysis of transcribed responses was then conducted by the Principal Investigator. Major themes were identified and reported. Additionaly, two questions, questions five and eight, were quantitative in nature and frequencies of responses were reported. This report highlights and synthesizes the responses to each of the interview questions developed for this study. Please see the Appendix for the full interview guide that was administered to the promotoras.

Question a. Please describe the Latinx population you work with in general as a promotora.

Working with Latinx communities from diverse regions of the state, promotora respondents engage clients from communities, including Snohomish, Bothell and Everett, Skagit County, including Bellingham, Vancouver, WA and Grandview and West Valley in Yakima County. Five of the promotoras revealed working in rural communities, with 3 of them specifically mentioned working with agricultural workers. Several mentioned working with elderly individuals.

Question 1. Focusing on this Latinx population, what do you consider to be their general attitudes/opinions on the use and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines?

Overall, mixed reactions among their Latinx clients were noted by the respondents regarding the use and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, with differences largely noted based on urban and rural context of the community.

Among urban respondents, the identified general attitudes on the use and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines reflected an openness to information and updates and belief in their effectiveness. However, with regards to trust of the vaccines, religious beliefs may play a role with regards to the identified skepticism.

In my Latin church community, there is more skepticism. I would say that about 50% are in favor of vaccines there.

I believe half of the people trust vaccines, while the other half believe they are ineffective or unnecessary.

Reasons offered by one promotora regarding this lack of trust centered on lack of education and misinformation.

They believe COVID is just a regular flu and vaccines are a form of state control.

The promotoras working with rural Latinx individuals and communities, on the other hand, revealed a stronger trust regarding COVID-19 vaccines, indicating that a majority want to get vaccinated. An important motivation revealed by one respondent was the desire to travel.

I think at the beginning we started seeing more and more people requesting the vaccines because they wanted to travel to Mexico and that was a requirement for them to travel.

Another motivating factor was the desire to be healthy in order to work.

They want to be healthy to keep working. If the medical provider recommends it, they get it because they want to be healthy.

An important finding was that initial hesitancy towards obtaining the vaccine in rural areas gave way in many instances to clients eventually getting vaccinated.

At first, nobody wanted to get vaccinated; it was challenging to convince them. However, as they realized the severity of the disease and the necessity of the vaccine, we started seeing many patients, especially older individuals, wanting to get vaccinated.

Overall, the respondents provide a snapshot of the diverse range of opinions on the use and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines. It highlights the importance of addressing vaccine hesitancy through education, outreach, and clear communication about the benefits and risks of vaccination.

Question 2. Can you name the top two reasons that influences the decision of your Latinx clients to receive a COVID-19 vaccine shot?

Protection—personal and family (75%)—and work, whether from a mandate or from a need to work to provide for families (37.5%), were the top two reasons noted by the respondents to this question. Of particular note, the desire to protect elderly family members was mentioned by a few respondents.

Other reasons cited include fear of getting sick (25%) and desire to travel (12.5%). The desire to travel is a new finding in this study. It was not reported by the respondents in the original study.

A recommendation that emerged in one of respondents’ answers to this question warrants attention, namely, the positive role financial incentives can play.

Incentives such as money or gift cards could be helpful because sometimes they lack the time or knowledge to schedule a vaccine appointment.

Question 3. Can you name the top 2 reasons that influence the decision of your Latinx clients NOT to receive a COVID-19 vaccine shot?

Responses to this question were very congruent with the findings in our previous report. The top reason for NOT receiving a COVID-19 vaccine was fear of side effects (75%).

I think the idea of them getting sick the following date after getting the shot is a big reason because they don’t want to stop working or feel down when they are so busy and have many things to do.

One new finding is that many felt that COVID-19 vaccination was unnecessary (37.5%).

Because they felt it was unnecessary, that COVID-19 was just a normal flu…They felt that they didn’t need it. They rely on many home remedies like teas, so they chose not to get vaccinated because, in their view, it wasn’t necessary.

This finding warrants attention in the planning of the media campaign. Providing clear examples of the benefits, values, and effectiveness for self and the community in obtaining a COVID-19 vaccination is critical and highly recommended.

Twenty-five percent of the respondents reported doubts of the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine as a contributing reason for not obtaining it.

Question 4. Focusing on the Latinx clients/community you work with as a promotora, what do you see as the primary source of information for staying updated with news overall for these Latinx clients/community?

Facebook was reported as the primary source of information by 75% of the respondents. Spanish language media, such as television (50%) and radio (37.5%), were also identified as important information sources. To a much lesser extent, social media platforms such as Tik Tok and providers were each identified by one respondent each. Within rural communities, promotoras indicated that 60% of clients rely on Facebook with the same percentage relying on television.

Question 4.1 Is there a specific TV show or social media account that they listen to or read more frequently?

Three respondents indicated that the Spanish language television station, Univision, was viewed most frequently. Another three expressed that their clients/communities did not have a specific TV show or social media account that they listened to or read more frequently. Two respondents identified local Spanish language radio programs while one revealed another Spanish language television station, Telemundo, and social media.

It is good to note that one urban respondent remarked:

On Facebook, many use Health Washington or community pages.

Question 5. For the Latinx client/community you work with, what sources of information do they seek out or use when it comes to staying informed about COVID-19? Please answer yes or no to each of the following prompts.

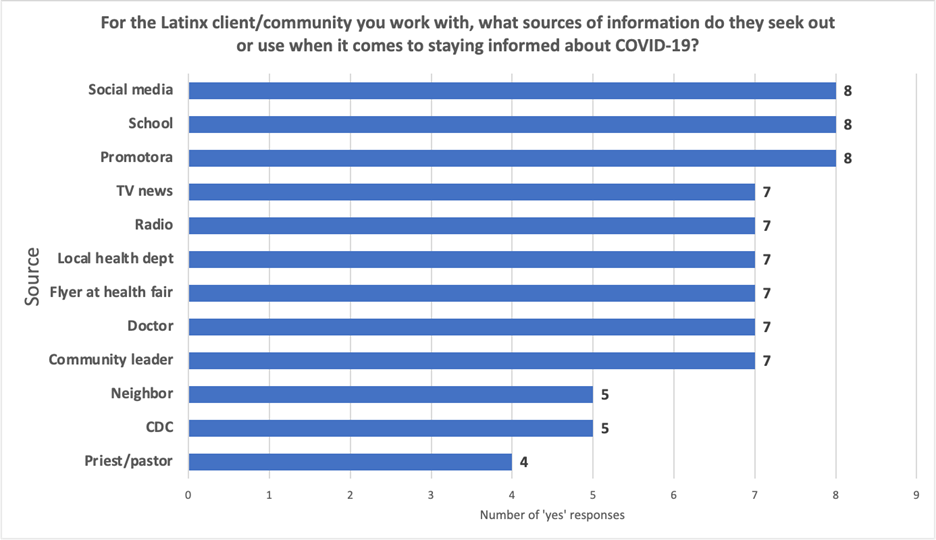

This question enabled a quantitative analysis where promotoras indicated various information sources used by the community they serve to stay informed about COVID-19. The graph above indicates that social media, school, and recommendations from a promotora were the most commonly used sources of information among their Latinx clients—each receiving a 100% response. Participants also reported that their clients often relied on TV news, radio, local Health Department, flyer at a health fair, doctor and a community leader as important sources of information. Each highly ranked with 87%. The least common sources reported were priest/pastor, the CDC, and a neighbor.

These findings indicate that Latinx communities rely on various sources to stay informed about COVID-19. Social media, traditional media such as radio or TV, and trusted community sources like promotoras and health professionals all play a valuable role in keeping Latinx communities informed. Additionally, the findings highlight the significant role of schools in building trust and influencing perceptions among the Latinx clients with whom promotoras work. This finding is noteworthy as schools were not ranked at all in the original study. Similarly, this study’s finding also emphasizes the widespread use of social media platforms among Latinx individuals in both rural and urban areas as trusted sources of information. Therefore, it is recommended that future media campaigns adopt a multifaceted approach, utilizing various media platforms to effectively disseminate information.

______________________________________________________________________

Question 5 b. Of these trusted sources of information you indicated, what are the top 3 messengers Latinx community members trust for COVID-19 related information? e.g. information from the radio, doctors, church leaders, community leaders, promotoras de salud, schools?

____________________________________________________________________________________

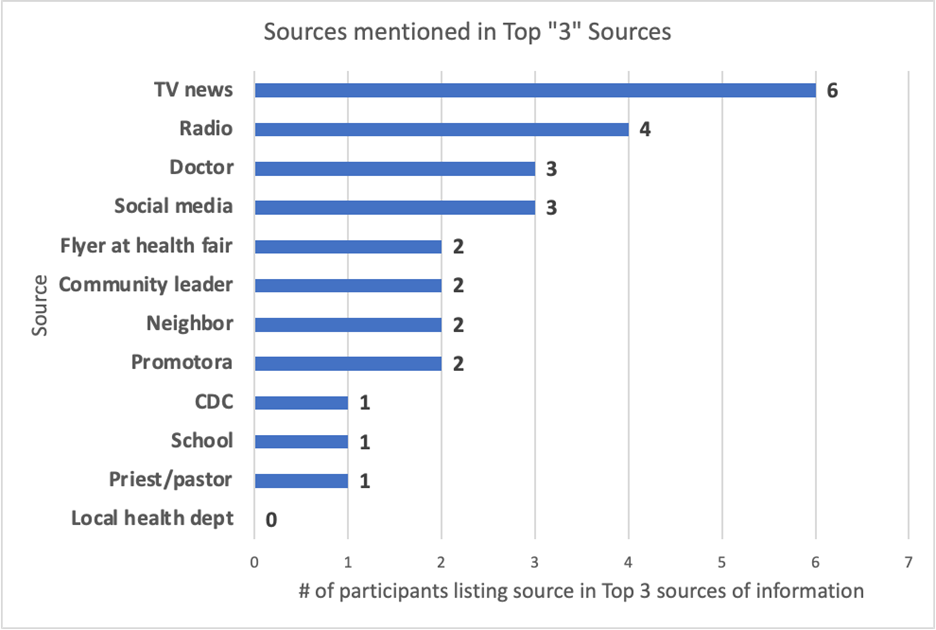

When promotoras were asked to rank the top three sources of information used by their Latinx clients, we found a different trend. Here, TV news emerged as the most unanimous answer, with 75% of promotoras mentioning it among the top three sources. Radio followed closely behind, with 50% of promotoras considering it among the top three. This suggests that traditional media sources may be playing a large role in shaping Latinx communities’ understanding of COVID-19. Doctors were also highly ranked within the top three sources as they are crucial sources and viaducts of disseminating up-to-date information regarding COVID-19 and vaccinations to the Latinx community.

At the bottom of the ranking of top 3 sources of information, in each case only one promotora mentioned the CDC, school, and pastor/priest. Significantly, none of them mentioned the local health department. This is noteworthy as it is a finding contrary to the high ranking reported in the original report with 25 respondents as well as the high ranking (87.5%) reported by the promotoras in the previous question in this report.

Interpretation of this finding should be done with caution as it stems from a small sample size. However, the results point to an important opportunity for the Department of Health to make effective use of Spanish and English communication efforts, including on local radio programs, to make visible its health promoting work and elevate its collaboration with local resources, including doctors and promotoras.

One participant, who identified neighbors as one of the top three sources used for their clients, remarked, “I think they are a very strong community, and they are influenced a lot by other community members.” This statement underscores the cohesive nature of Latinx communities, where opinions and experiences hold significant weight. It suggests that information and behaviors can rapidly disseminate through interpersonal networks within the Latinx community, emphasizing the importance of community-driven initiatives and communication strategies in effectively reaching and engaging this population.

Question 6. What are beliefs and conceptions/perceptions towards COVID-19 vaccines that you have heard about or find in the Latinx community you work with?

This question elicited a range of responses from deeming the vaccines as unnecessary, to not understanding the need for more doses or booster shots, to openness to getting vaccinated and viewing positive aspects of vaccination.

Regarding the boosters, there isn’t as much interest as before. Many think it’s unnecessary medicine, something the government is doing without it actually working.

I think a lot of people stop having the doses after the third dose. Many do not understand why they need more doses, or I think they are busy and think “well I already had three doses; I think that’s enough”.

I believe that as long as people receive information about vaccines, they are open to getting vaccinated. There are many who are willing to educate themselves and learn.

Other notable responses include mistrust due to the vaccines serving to implant a chip into the recipient, the belief that natural immunity is sufficient, and that the vaccine can alter a person’s DNA.

I have heard some people talking about the idea that a chip is being implanted and that natural immunity is sufficient.

There is also a myth that I heard, saying that vaccines could change your DNA because they inject the virus DNA, and that’s why it’s not good to vaccinate anyone.

One respondent indicated that some in the community note positive aspects of the COVID-19 vaccine.

I’ve also heard positive things, like they help prevent illness or reduce the risk of getting the virus, especially for those living with older adults or children.

Another promotora identified several obstacles pertaining to the COVID-19 vaccinations.

I have heard that there are people who want to get vaccinated but don’t know where to go or if they will be charged.

This response reveals a clear opportunity for the DOH to address and provide concrete information regarding the accessibility of the COVID-19 vaccine and to clarify whether any costs are involved in receiving it.

Another respondent provided the following statement regarding the vaccine most trusted within the community.

I also consider that they have the most confidence in the Pfizer vaccine, and the Johnson & Johnson vaccine is the least accepted by my clients; they feel it is the least effective.

Question 7. What message or information would make the Latinx community you work with more inclined to consider getting a COVID-19 vaccination?

The promotoras answers to this question provide important insights and considerations regarding focus of information as well as use of family images when messaging the Latinx community.

I think that the media, social networks, and others should promote information about COVID mortality rates or how common Long COVID is. Show that the disease is severe and it is necessary to protect ourselves because more people are dying from COVID than from vaccine-related effects. I also believe that portraying a family image would be helpful, and airing these messages at convenient times would be even more effective.

I believe that an image of a Latinx family would generate more confidence in them.

Cost is an important factor to address.

If promoting it as free, it would be good to specify where it can be obtained for free. I know of people who had to pay to get vaccinated.

Convenient hours, and the fact that they are free, would also be beneficial.

Incentivizing them through monetary means is effective, as many Latinos come here with a focus on working to support their families. Taking time off work to get vaccinated or having to take a day off to rest because you might feel a bit unwell the day after the vaccine is a concern in the Latino community. When there’s a monetary incentive, many may think, ‘Well, I can take time to get the vaccine, which is also important, but I’m earning extra that can continue to help with expenses.

Useful recommendations for the media campaign include:

I suggest providing more information about the symptoms, what the vaccine does and doesn’t do, why it works, and what the vaccine contains. Explaining why it’s necessary to get vaccinated every year is important. Regarding the examples given, including images of families, and emphasizing that the vaccines are safe for children would be quite helpful.

Question 8. Now, I am going to ask you about how much you agree or disagree with a series of statements about vaccines in general, not just COVID-19 vaccines. Again, you are focusing on the Latinx clients you work with as a promotora. For each statement, there are five options: strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree, or ‘I’m not sure.’ How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statement?

| English | Spanish |

| Statement 1: There are ways to access vaccines convenient for my work and family schedule, including mobile, school, and community-based vaccine clinics and pharmacies that are open seven days a week or in the evenings. | Afirmación 1: Hay formas de acceder a vacunas convenientes para mi horario laboral y familiar, incluyendo clínicas de vacunación móviles, en escuelas y comunidades, así como farmacias abiertas los siete días de la semana o en las noches. |

| Statement 2: Most vaccines (including COVID and Flu) are available to children and adults in Washington at no- or low cost. There are easy-to-access programs to cover the cost, regardless of insurance status. | Afirmación 2: La mayoría de las vacunas (incluyendo las de la COVID y la gripe) están disponibles para niños y adultos en Washington sin costo o a bajo costo. Hay programas de fácil acceso para cubrir los costos, independientemente del estado del seguro médico. |

| Statement 3: Natural immunity isn’t enough to protect individuals and communities from serious diseases, so we need a boost from vaccine immunity to help keep everyone safe. | Afirmación 3: La inmunidad natural no es suficiente para proteger a individuos y comunidades de enfermedades graves, por lo que necesitamos un impulso de la inmunidad a través de las vacunas para ayudar a mantener a todos a salvo. |

| Statement 4: By getting routine and seasonal vaccines, I’m giving myself extra protection but maybe more importantly, I’m helping protect everyone in my family. | Afirmación 4: Al vacunarme regularmente y en temporada, me estoy brindando una protección adicional, pero quizás más importante aún, estoy ayudando a proteger a todos en mi familia. |

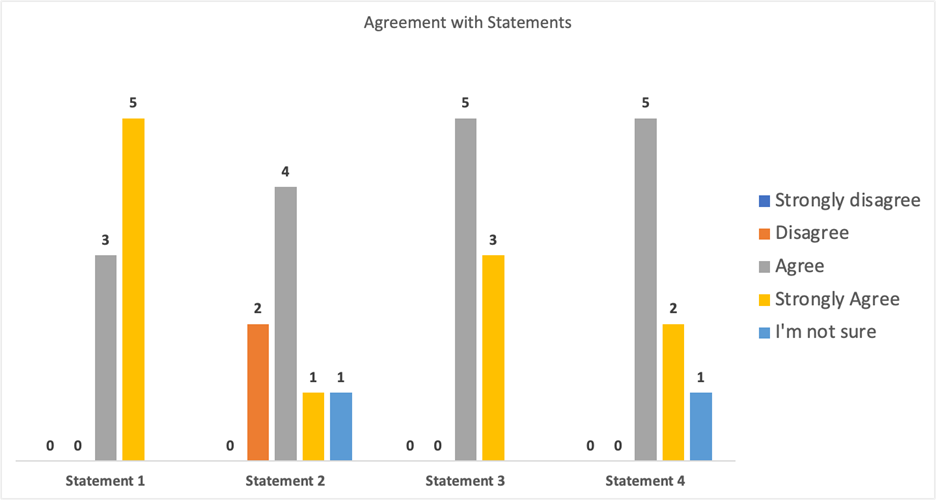

The analysis of the graph depicting responses to statements about vaccines reveals several key insights. One, all respondents unanimously agreed or strongly agreed with statements one and three, indicating a pervasive positive attitude or strong belief in the content of these statements. Two, statement two elicited a more mixed response, with five respondents agreeing or strongly agreeing, but two participants expressing disagreement. This suggests a more varied perspective or level of agreement on this particular statement compared to the others.

Statement four garnered substantial support, as nearly all respondents agreed or strongly agreed with it (7). Interestingly, both statements two and four also received one response each of “I’m not sure,” indicating some level of uncertainty or lack of strong opinion among respondents regarding these statements.

Overall, the analysis highlights a generally positive attitude towards statements one, three, and four, with statement two receiving a more mixed response due to a more diverse range of opinions.

| Strongly disagree | Disagree | Agree | Strongly Agree | I’m not sure | |

| Statement 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Statement 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Statement 3 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 |

| Statement 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 1 |

Analyzing responses to statements about vaccines reveals distinct trends within the Latinx community. Accessibility emerges as a prominent theme, as evidenced by the unanimous agreement with Statement 1, indicating a strong belief in the availability of convenient options such as mobile clinics and extended pharmacy hours. However, perceptions of cost and availability present a more nuanced picture. The mixed response to Statement 2 suggests potential gaps in knowledge regarding programs that cover vaccine costs.

For Statement 3, a unanimous agreement underscores a shared belief in the necessity of vaccine-induced immunity for safeguarding individuals and, Statement 4 with significant support, indicates a recognition of the collective benefits of routine vaccinations, which extend protection beyond individuals to families and communities. In summary, the findings portray a generally positive outlook within the Latinx community, emphasizing the importance of accessibility, immunity, and community protection. However, the mixed perceptions regarding cost and availability emphasize the need for targeted outreach and education to ensure equitable access.

CONCLUSION

This small qualitative study provides valuable insights into the perspectives of Latinx community health workers (promotoras) regarding the perceptions and attitudes of Latinx individuals and communities with whom they work pertaining to COVID-19 vaccines. The main themes identified in this study contribute to a culturally informed understanding that can help inform the planned media campaign of the Department of Health.

Throughout the pandemic, many Latinx individuals have struggled with divergent communication and misinformation regarding the COVID-19 disease and vaccination options and their side effects. Concerns persisted about the effectiveness and side effects of the vaccinations. These concerns and fears remain and continue to impact the health of the Latinx community.

Federal and state agencies are investing less money and resources to address COVID-19 and its deleterious impacts. In light of the data in this report and the original report, coupled with data pertaining to the sizeable number of individuals suffering from long COVID, such disinvestment seems foolish. As identified in this study, an undeniable need exists to communicate clear and trusted information in English and Spanish across the diverse Latinx population in Washington state regarding the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccinations. Study findings reveal that some people who are hesitant to get vaccinated often lack information about how they work. This suggests that culturally responsive education and strategic outreach efforts could be helpful in increasing vaccine uptake by Latinx individuals.

Aligned with the findings from the original study, this study also highlights the importance of addressing the family and not just the individual in the planned media campaign. Such an approach is congruent with the cultural value of familismo within the collectivist culture of the diverse Latinx community. Thus, images of family members getting vaccinated and smiling with the knowledge that they are protecting themselves from serious consequences of COVID-19 and promoting health for themselves, other family members, including elders, and their community should be designed and well-utilized in DOH media efforts to the Latinx community.

In summary, the main themes identified by the promotoras include:

- Protection of Family: Most respondents stated that their Latinx clients’ primary motivation for getting vaccinated was the protection of their families.

- Fear of Vaccine Side Effects: This fear persists in Latinx communities in WA state. The predominant fear was the potential side effects of vaccines.

- Hesitancy giving way to obtaining vaccinations: This finding identified an openness by a number of Latinx adults to vaccinations that supports educational efforts.

Based on this study’s findings, investing in education about vaccines, clarifying what they do and how do they work is a clear investment that should be undertaken by the Department of Health. The identified receptivity over time to obtaining vaccinations calls for a staunch commitment and a robust investment of resources by the Department of Health to educate and communicate about the importance and health benefits of COVID-19 vaccinations to the Latinx population that is at heightened risk of contracting COVID-19. Indeed, employing culturally responsive efforts can have significant impacts in promoting health across urban and rural Latinx communities in Washington state.

Findings reveal various sources of information that Latinx individuals often seek out or use when it comes to staying informed about COVID-19, including social media, schools, promotoras, Spanish and English language radio and television outlets, local departments of health, flyers at health fairs and doctors. These approaches are affirmed to be effective and should be utilized in the Department’s media campaign as well as its educational and outreach efforts. Making strategic use of its own website with current information presented in Spanish and English languages is another effort to implement. As previously noted, the themes of safety and protection of family should be central messages.

REFERENCES

1. Kekatos, M. (Jan. 10, 2024). Why are 1500 Americans still dying from COVID every week, ABC news. Accessed: January 13, 2024).

2. Kekatos, M. (Jan. 10, 2024). Why are 1500 Americans still dying from COVID every week, ABC news. Accessed: January 13, 2024).

- Latino Center for Health, University of Washington (2021). Vaccination Rates Among Washington State’s Latinos Are Improving, But Challenges Remain. https:// latinocenterforhealth.org/ wordpress_latcntr/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/ DRAFTv2_VaccinationRatesOctober2021.pdf).

- influenza vaccination data. (n.d.). Washington State Department of Health. https://doh.wa.gov/data-statistical-reports/health-behaviors/immunization/influenza-vaccination-data Accessed January 17, 2024.

- Morales, L. (2024). Long COVID Among Latinos in Washington State. Unpublished manuscript. Latino Center for Health, University of Washington.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Gino Aisenberg, co-Director of the Latino Center for Health, was Principal Investigator of this study. In the writing of this report, Luisana Valero, Student Assistant with the Latino Center for Health, also made significant contributions and is co-author of this report.

A special thanks to Dr. Ileana Ponce-Gonzalez, Executive Director, of Community Health Worker Coalition for Migrants and Refugees and Mary O’Brien, Clinical Services Director of Behavioral Health Services at the Yakima Valley Farm Workers Clinic. Both were instrumental in helping us identify and recruit participants in this study.

APPENDIX

LCH DOH Qualitative Interview Script—COVID-19 and Test Messages

Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me today. My name is Luisana, and I am a Research Assistant for the Latino Center for Health at the University of Washington. The Center is working with the WA State Department of Health to understand the perspectives and attitudes of Latinos towards vaccines and to inform the media campaign messaging of the Department of Health. There are no right or wrong answers.

Your responses to this interview are confidential and will not be shared with anyone outside the research team. This interview is completely voluntary. You may choose not to answer any questions you prefer not to answer. The interview will take approximately 30 minutes and we will send you a $40 gift card after completing the interview as a thank you for your participation and compensation for your time. The focus of these interview questions is on COVID-19 vaccines.

What you say to us is important, so we’d like to take notes. To make sure our notes correctly represent what you say, we would also like to take a sound recording. The recording is confidential and will not be shared with anyone outside of the Latino Center for Health. We will destroy the recording at the end of February 2024. If you have no objections, we’ll proceed with the questions.

We will be asking questions, not about your own personal experience, but rather about your understanding of the overall perspectives/experiences/attitudes of Latinx individuals with whom you work as a promotora. Thank you for being willing to participate. We hope that we can take what you share to the WA Department of Health to help us understand better the needs and desires of our Latinx community.

Before we start with the main portion of the interview, I would like to ask if you could answer two short-ended questions about yourself. You may decline to answer any of these.

- What is your preferred language?

- Please describe the Latinx population you work with in general as a promotora.

- Focusing on this Latinx population, what do you consider to be their general attitudes/opinions on the use and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines?

I know this can be a sensitive topic, but we welcome and respect all types of perspectives. Please share your honest thoughts and feelings about the Latinx community you work with regarding their use of COVID-19 vaccines and their effectiveness.

- Can you name the top 2 reasons that influences the decision of your Latinx clients to receive a COVID-19 vaccine shot?

(Note: these are f/u prompts: Perhaps the desire to protect their family, friends, community, personal health protection, fear of hospitalization, easy to get vaccine, trust that it is safe, because it was a mandate, all possible options are welcome.

- Can you name the top 2 reasons that influences the decision of your Latinx clients NOT to receive a COVID-vaccine shot?

(Note: these are f/u prompts: For example, it could be the they don’t believe vaccines are safe, fear of side effects, they don’t have confidence in their effectiveness, don’t think that the risk of getting COVID-19 is that high, they have concern that the vaccine affects their fertility, concern that vaccines cause autism, or the difficulty to get the vaccine due to their work schedule, or lack of transportation to get to appointment for vaccination. Feel free to be honest, all possible reasons are welcome and accepted.

- Focusing on the Latinx clients/community you work with as a promotora, what do you see as the primary source of information for staying updated with news overall for these Latinx clients/community?

- Options: TV, radio, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp group chats, text messages, telegram, newspaper, or other.

- Is there a specific tv show, or social media account that they listen to or read more frequently?

- Options: TV, radio, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp group chats, text messages, telegram, newspaper, or other.

- For the Latinx client/community you work with, what sources of information do they seek out or use when it comes to staying informed about COVID-19? Please answer yes or no to each of the following prompts.

- Options:

- CDC guidelines ___Yes ___No

- What the local health department said ___Yes ___No

- What they heard on TV news ___Yes ___No

- What a leader of your community said ___Yes ___No

- What the priest or pastor said ___Yes ___No

- What the school said ___Yes ___No

- What a flyer said at a health fair ___Yes ___No

- What their doctor said ___Yes ___No

- What a promotora de salud said ___Yes ___No

- What they heard on the radio? ___Yes ___No

- What they learned from social media? ___Yes ___No

- What a neighbor told them ___Yes ___No

- Options:

- Of these trusted sources of information you indicated, what are the top 3 messengers Latinx community members actually trust for COVID-19 related information? e.g. information from the radio, doctors, church leaders, community leaders, promotoras de salud, schools?

- What are beliefs and conceptions/perceptions towards COVID-19 vaccines that you have heard about or find in the Latinx community you work with?

- What message or information would make the Latinx community you work with more inclined to consider getting a COVID-19 vaccination? For example, if they saw a picture of a family receiving the vaccine or heard a radio announcement explaining how COVID-19 vaccines are safe for children, are available free of cost, are available at a time that is convenient for them; would that or anything similar influence their decision?

- Now, I am going to ask you about how much you agree or disagree with a series of statements about vaccines in general, not just COVID_19 vaccines. Again, you are focusing on the Latinx clients you works with as a promotora. For each statement, there are five options: strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree, or ‘I’m not sure.’

Do you have any questions?

- How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statement? (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree, I’m not sure)

Statement 1: There are ways to access vaccines convenient for the work and family schedules of your Latinx clients, including mobile, school, and community-based vaccine clinics and pharmacies that are open seven days a week or in the evenings.

___Strongly Disagree ___Disagree ___Agree. ___ Strongly Agree. ___I’m not sure

Statement 2: Among the Latinx clients you work with, most believe thatmost vaccines (including COVID and Flu) are available to children and adults in Washington at no- or low cost. There are easy-to-access programs to cover the cost, regardless of insurance status.

___Strongly Disagree ___Disagree ___Agree. ___ Strongly Agree. ___I’m not sure

Statement 3: Among the Latinx clients you work with, most believe that natural immunity isn’t enough to protect individuals and communities from serious diseases, so we need a boost from vaccine immunity to help keep everyone safe.

___Strongly Disagree ___Disagree ___Agree. ___ Strongly Agree. ___I’m not sure

Statement 4: By getting routine and seasonal vaccines, most Latino clients you work with believe that by they are giving themselves extra protection but maybe more importantly, they are helping protect everyone in their family.

___Strongly Disagree ___Disagree ___Agree. ___ Strongly Agree. ___I’m not sure

That concludes the questions we have for you today.

Do you have any additional questions or thoughts you would like to share with us? We sincerely appreciate your participation and the insights you have provided; your time and commitment are highly valued by our team.